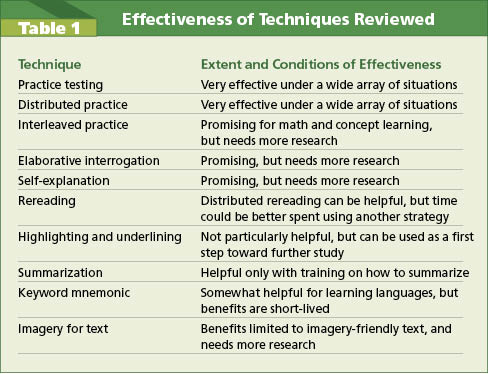

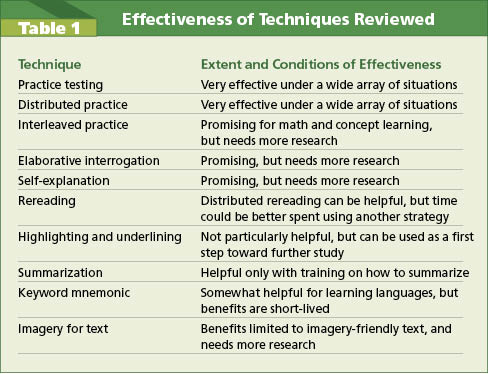

The most effective study strategies–practice testing and distributed practice–are not sufficiently taught or emphasized by teachers. That is the conclusion reached by John Dunlosky of Kent State University, who lead a team of researchers that included Daniel Willingham in reviewing the efficacy of various learning strategies.

Part of the problem lies with schools of education, where “teacher preparation typically does not emphasize the importance of teaching students to use effective learning strategies”. This seems ironic, considering how fervently educators promote “lifelong learning” as a 21st century skill.

Details about the two most effective study techniques:

1. Practice testing: self-testing or taking practice tests on to-be-learned material.

Students and teachers can use practice testing in several ways.

… First, student learning can benefit from almost any kind of practice test, whether it involves completing a short essay where students need to retrieve content from memory or answering questions in a multiple-choice format. Research suggests, however, that students will benefit most from tests that require recall from memory, and not from tests that merely ask them to recognize the correct answer….

Second, students should be encouraged to take notes in a manner that will foster practice tests. For instance, as they read a chapter in their textbook, they should be encouraged to make flashcards, with the key term on one side and the correct answer on the other. When taking notes in class, teachers should encourage students to leave room on each page (or on the back pages of notes) for practice tests….

Third, and perhaps most important, students should continue testing themselves, with feedback, until they correctly recall each concept at least once from memory. For flashcards, if they correctly recall an answer, they can pull the card from the stack; if they do not recall it correctly, they should place it at the back of the stack. For notes, they should try to recall all of the important ideas and concepts from memory, and then go back through their notes once again and attempt to correctly recall anything they did not get right during their first pass….

Not only can students benefit from using practice tests when studying alone, but teachers can give practice tests in the classroom….

I notice that some local high school math teachers don’t give quizzes or grade homework, both of which would help student learning and serve as valuable formative assessment by providing feedback that could improve instruction.

2. Distributed practice: implementing a schedule of practice that spreads out study activities over time.

Students use this method naturally in other endeavors such as sports or music.

… In these and many other cases, students realize that more practice or play during a current session will not help much, and they may even see their performance weaken near the end of a session, so, of course, they take a break and return to the activity later. However, for whatever reason, students don’t typically use distributed practice as they work toward mastering course content.

What teachers can do:

To use distributed practice successfully, teachers should focus on helping students map out how many study sessions they will need before an exam, when those sessions should take place (such as which evenings of the week), and what they should practice during each session. For any given class, two short study blocks per week may be enough to begin studying new material and to restudy previously covered material…..

Teachers can also use distributed practice in the classroom. The idea is to return to the most important material and concepts repeatedly across class days. For instance, if weekly quizzes are already being administered, a teacher could easily include content that repeats across quizzes so students will relearn some concepts in a distributed manner. Repeating key points across lectures not only highlights the importance of the content but also gives students distributed practice….

I’m a little surprised that summarization is not a very effective study technique. While it might seem to be a form of practice testing, in reality it only helps “with training how to summarize”.