The question of whether the federal government profits from student loans has come up recently in discussions about the various proposals to prevent the scheduled Stafford subsidized loan rates from doubling to 6.8% on July 1. This question puzzled me when I wrote about it last November. At that time I found conflicting accounts, which frankly made my brain hurt. Since I was left with a lingering curiosity about these illusive profits, the recent discussions on the topic caught my attention.

On May 16 the Huffington Post reported of projected federal profits exceeding those of Exxon, Apple, and other corporate giants.

Figures made public Tuesday by the Congressional Budget Office show that the nonpartisan agency increased its 2013 fiscal year profit forecast for the Department of Education by 43 percent to $50.6 billion from its February estimate of $35.5 billion.…

The Education Department has generated nearly $120 billion in profit off student borrowers over the last five fiscal years, budget documents show, thanks to record relative interest rates on loans as well as the agency’s aggressive efforts to collect defaulted debt.

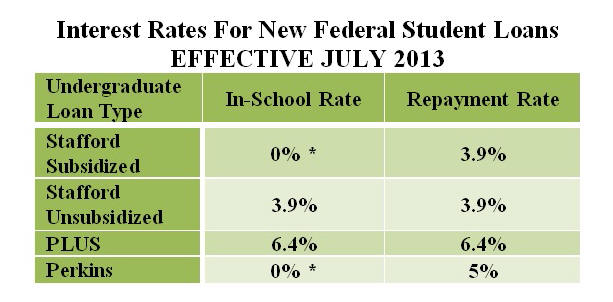

But that rate is set to double to 6.8 percent, the rate for unsubsidized loans (for richer students, or poor students with debt above the subsidized loan program’s limits), on July 1.

The Washington Post, in reporting on the political disagreements in Congress, referenced the DOE’s $51 billion projected profit.

Democrats … objected to increasing the rates within a program that generates vast income for the federal government. The Congressional Budget Office this week revised its figures this week, reporting that federal loans will generate almost $51 billion this year. Over the last five years, that sum is almost $120 billion.

“That $51 billion is more than Exxon,” Miller said.

“It’s time we stop using federal student loans as a profit center,” added Rep. John Tierney, D-Mass.

Writing for Yahoo Finance, Jason Delisle disputes this notion of student loan profits, pointing out that the high risk of default must be considered.

What about Senator Warren’s claim that the government makes money off loans to low-income students? Senator Warren is not telling the whole story here either. She points to figures that the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office says “do not provide a comprehensive measure of what federal credit programs actually cost the government and, by extension, taxpayers.” In fact, when the budget office “accounts more fully… for the cost of the risk the government takes on when issuing loans,” it reports that Subsidized Stafford loans – those made to low-income students – cost taxpayers $12 for every $100 lent out, or $3.5 billion per year….

The claim that the government makes money on these loans is even more dubious given that the Department of Education estimates that 23 percent of the Subsidized Stafford loans it makes this year will default. That puts it among the riskiest loan programs that the federal government runs. By comparison, about 7 percent of the loans under the Federal Housing Administration mortgage program are expected to default. That program provides loans to high-risk borrowers who do not qualify for a traditional mortgage because they lack the savings, income or credit history.

Finally, in the May 20 Washington Post WonkBlog Dylan Matthews concludes that the “federal government does not profit off student loans”, at least not “in some years”.

Matthews reiterates that the interest rates do not reflect market risk.

… they set the interest rate on student loans below the market rate. And because they’re below the market rate, that costs the federal government money. Contrary to popular belief, and many a breathless article, the government does not, in fact, book a profit on student loans. As New America’s Jason Delisle has explained, that’s because the Congressional Budget Office is required by law to use a bizarre and faulty method for determining the cost of government loans.

Matthews goes on to explain what is essentially an unresolved dispute on the profitability of government student loans. Additional details complicate the picture. For example, even according to the CBO’s “bizarre and faulty” calculations, some years with higher subsidies actually show a loss.

I suspect there’s no profit.

After reading all these explanations, the most definitive statement I will accept is that it appears the government does not make a profit on student loans, but it might depend on the level of subsidies for any given year. As the headline says, it’s complicated.