The National Society of Scholars has compiled One Hundred Great Ideas for Higher Education.

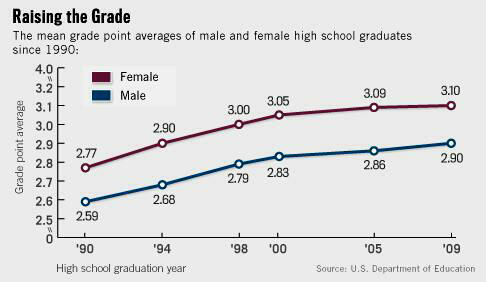

Despite the wide variety of suggestions, the list naturally organizes itself into a few common themes. Some of the themes are frequently mentioned in higher education circles, while others are rather surprising or novel. The most frequently cited category of suggestions called for some sort of renewed emphasis on the study of Western civilization, American history, or the classics of Western thought. Some of the other frequently discussed topics concern improving students’ writing skills, increasing transparency, combating political bias or correctness, and raising standards (including ending grade inflation).

In skimming through the list it’s hard to pick favorites, but here are a few that seem sensible.

This one addresses grade inflation.

REPORT CLASS GRADES

Richard Arum, Professor of Sociology and Education, New York University

Colleges and universities could administratively address the problem of declining academic rigor by instituting a simple change: for every course a student takes, the student’s transcript would report the individual grade received as well as the average grade students received in the course. The transcript would also report the overall grade point average (GPA) of the student as well as the course grade point average (CGPA).

Without impinging in any way on either the ability of individual faculty to grade students as they choose or the freedom of students to select courses as they see fit, this administrative reporting change would make readily apparent whether a student excelled at coursework, or instead excelled at choosing a path through higher education that held students in relative terms to lower academic standards. Incentives for faculty to grade leniently and for students to choose easy coursework—which has led the academy in recent years to a “race to the bottom”—would be significantly reduced.

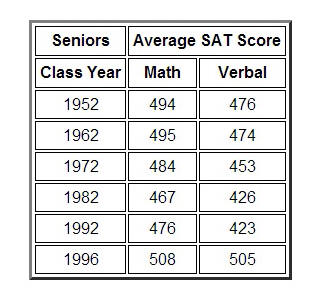

Examining post-college transitions of recent college graduates, Josipa Roksa and I have found that course transcripts are seldom considered by employers in the hiring process. Transcripts would be significantly more meaningful with this simple and relatively costless administrative reporting change. If colleges and universities did not have the political will to make such changes on their own, access to federal financial aid dollars could be made dependent on institutional compliance. More than one-third of college students today study alone for their classes less than an hour per day and yet are able to achieve a 3.2 GPA. Parents, employers, and students have a right to know how this type of college success is accomplished.

Teach students how to write.

INSTITUTE EXIT EXAM IN WRITING

Lawrence Mead, Professor of Politics and Public Policy, New York University

The great scandal of American education is that students can complete their schooling without learning to write correct prose. Even at the college level, and at good schools, most students cannot write even a page of text without committing some error of grammar, usage, or spelling. This is apart from content. The reason is that their teachers—from kindergarten all the way through—have little interest in correcting these errors. Either they themselves don’t know how to write, or it’s too much work.

Professors have no personal or professional interest in whether their students write well, so they ignore the problems and pass students along. College writing programs have little impact on the problem. But once on the job students quickly discover that the boss is their coauthor as their teacher was not, demanding that they be able to write letters or reports that he can sign without embarrassment—or be fired.

I recommend instituting a writing exam that undergraduates must pass to graduate from college, with rules for grammar and usage defined in advance. Ask students to respond to some essay question in, say, five pages, without outside help. Allow students some very small number of errors, or fail them. Have a nonprofit body—funded by all colleges and universities—that would operate separately from coursework correct and return the papers to students with errors indicated.

Allows students to take the test any number of times, but make the number of attempts to pass part of their academic record. Publicize these results by school, with the goal that they will eventually be factored into U.S. News & World Report rankings.

There are pros and cons to student evaluations, but they seem to have contributed to lower standards.

ABOLISH STUDENT EVALUATIONS

Jonathan Imber, Jean Glasscock Professor of Sociology, Wellesley College; Editor-in-Chief, Society

Many colleges and universities today use student evaluation questionnaires to evaluate a teacher’s performance. The origin of this seemingly benign tool has much to do with its abuse as a weapon of conformity. The student protesters of the 1960s demanded greater “participation” in the life of the university. Administrators saw an opportunity at appeasement that also translated into a mechanism for oversight, which in the long growth of university administration means the production of ever more information about everyone and everything. Students could be part of the process of “democratically” supporting or opposing such decisions as tenure and promotion.

The result has been granting permission to students to offer anonymously any kind of opinion they want to express, however inane or cruel. Of course, teachers ought to be able to take it, but consider how profoundly the reversal of fortune now is: it was once expected that students ought to be able to “take it,” that is, to respond to tough standards, to hard lessons, to failure, to anything that might contribute to the building of character. Now, the students must be treated carefully, and the teacher has been put into the dock. To improve teaching, abolish student evaluations of teachers.

Hmm . . . I think I like two out of three of these ideas.

CUT UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION IN HALF; LIMIT THE CURRICULUM; INSTITUTE A DRESS CODE

Tom Wolfe, Ph.D., American Studies, Yale, 1957; Author, Back to Blood

Three changes would make their college years more valuable to students:

1. Cut undergraduate education from four years to two. Oxford and Cambridge have only three years, and most Oxbridgers consider that one year too many. Four years marinates students in two years of entertaining sloth, creating unwanted habits much more difficult to remove than unwanted hair. Two years will put even the “greatest” universities on par with community colleges, benefiting both. Imagine how many eyes will open up like—swock!—umbrellas when they discover that community college students take the content of courses far more seriously than university undergraduates. Both will graduate with bachelor’s degrees, greatly increasing the value of a community college education.

2. Limit the curriculum, over the two years, to remedial education and core subjects—without ever uttering the words “remedial” and “core.” All students will be forced to take courses in history, rhetoric, algebra or statistics, biology, and sociology. Needless to say, the word “forced” is not to be mentioned, either. Rhetoric will slyly include basic grammar and drills such as parsing sentences—in addition to basic training in prose styles. “Grammar” and “drills” will be taboo terms, too.

3. Male students will have a dress code requiring long-sleeved cotton shirts (ties optional) and conventionally cut jackets—e.g., no jacket collars wider than the lapels—whenever they are on campus. Female students will abide by a dress code that, without saying so, makes it impossible to dress in the currently highly fashionable (among young women) slut style.

If the students complain that these codes make them look different from most other people their age, the reply is, “Now you’re catching on.”