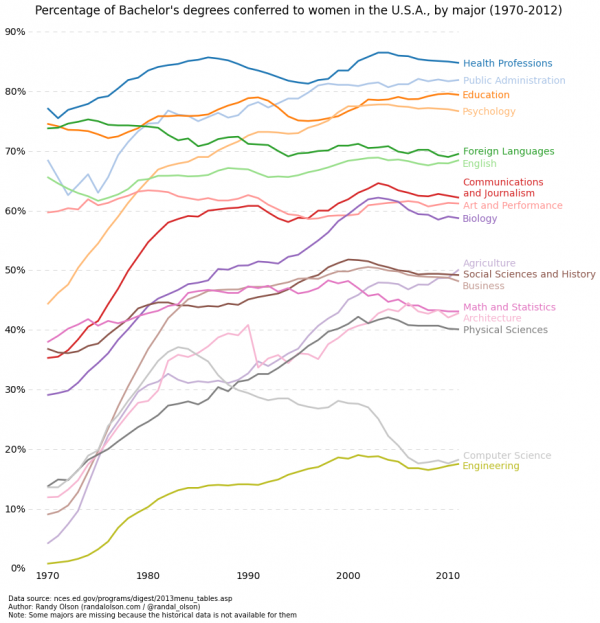

Randy Olson graphed the percentage of bachelor’s degrees conferred to women by major.

The only STEM gender gaps are in computer science and engineering.

Surprisingly to me, most of the STEM majors aren’t doing as bad gender disparity-wise as I expected. 40-45% of the degrees in Math, Statistics, and the Physical Sciences were conferred to women in 2012. Even better, a majority of Biology degrees in 2012 (58%) were earned by women. This data tells me that we don’t really have a STEM gender gap in the U.S.: we have an ET gender gap!

If we actually have a shortage in skilled engineering and technology employees, this gender gap matters.

This ET gender gap has severe consequences. Computer Science and Engineering majors have stagnated at less than 10% of all degrees conferred in the U.S. for the past decade, while the demand for employees with programming and engineering skills continue to outpace the supply every year…

Provided that far more women attend college than men, it seems the best way to meet the U.S.’s growing need for skilled programmers and engineers is to focus on recruiting more women — of any race or ethnicity — into Computer Science and Engineering majors. The big question, of course, is “How?” With the constant issues of subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) discrimination against women in these male-dominated majors, we have quite a tough task on our hands.

Looking at the historical trends, maybe we have something to learn from Architecture and the Physical Sciences, given that they were in our position only 40 years ago.

Geology, my field of study, has a similar story of declining gender imbalance.

… Between 1974 and 2000, geoscience degrees awarded to women rose from ~17% to 45% (AGI, 2001).

How did it happen?

Interestingly, the rise in women pursuing geoscience degrees coincided with a sharp decline in oil prices that decimated high-paying oil industry opportunities for geologists. At the same time, an increased interest in environmental issues pushed up the need for geologists to work in that area, often at jobs paid by government dollars either directly or indirectly. I think more women are attracted to those types of jobs than to the more rough-and-tumble ones in the oil or mining industries. I don’t see the possibility of a similar change in computer science or engineering where women would become newly attracted to those fields, thus shrinking the current gender gap.

Among the comments at Olson’s post was a suggestion that more female mentors were needed. And there was this:

When computer science programs incorporate soft skill training into the course content, i.e. communication, inclusion in a group, importance of teamwork, sexual harassment etc, you will see a change. Women have to see what the possibilities are for them in a field long term. If what they are seeing is a male dominated field, with people who do not communicate well, and who do not welcome them to the table, I don’t blame them for not choosing computer science. Women want to work where they are welcomed, where they can use both right and left brain skills.

Extensive group work and writing about math are examples of “soft” skills recently introduced in K-12 education, at least partly implemented as a means of improving the achievement levels of girls in math. I don’t believe the overall outcomes of this experimentation have been particularly positive, but perhaps it would work better at the college level.

———