Computers may soon be able to do white-collar jobs meant for college graduates.

Noriko Arai of the Todai Robot Project explains how the future is shaping up.

… a machine should be capable, with appropriate programming, of doing many — perhaps most — jobs now done by university graduates.

With the development of artificial intelligence, computers are starting to crack human skills like information summarization and language processing….

How would college graduates be affected by this technological evolution?

There is a significant danger, Ms. Arai says, that the widespread adoption of artificial intelligence, if not well managed, could lead to a radical restructuring of economic activity and the job market, outpacing the ability of social and education systems to adjust.

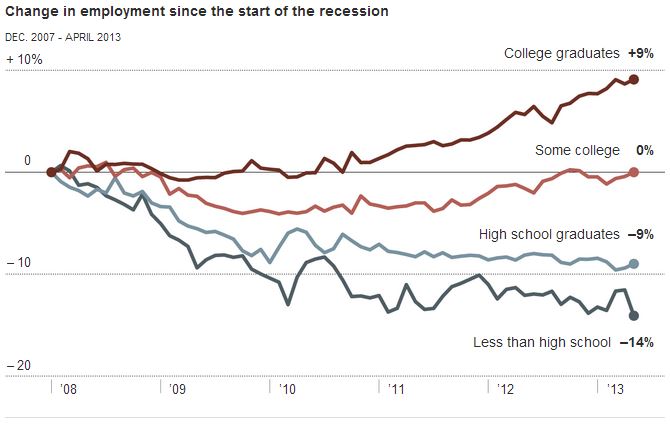

Intelligent machines could be used to replace expensive human resources, potentially undermining the economic value of much vocational education, Ms. Arai said.

“Educational investment will not be attractive to those without unique skills,” she said. Graduates, she noted, need to earn a return on their investment in training: “But instead they will lose jobs, replaced by information simulation. They will stay uneducated.”

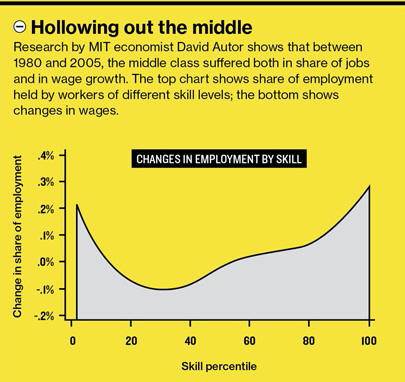

In such a scenario, high-salary jobs would remain for those equipped with problem-solving skills, she predicted. But many common tasks now done by college graduates might vanish.

Mostly good or mostly bad?

… A recent study published by the Program on the Impacts of Future Technology, at Oxford University’s Oxford Martin School, predicted that nearly half of all jobs in the United States could be replaced by computers over the next two decades.

Some researchers disagree. Kazumasa Oguro, professor of economics at Hosei University in Tokyo, argues that smart machines should increase employment. “Most economists believe in the principle of comparative advantage,” he said. “Smart machines would help create 20 percent new white-collar jobs because they expand the economy. That’s comparative advantage.”

Others are less sanguine. Noriyuki Yanagawa, professor of economics at Tokyo University, says that Japan, with its large service sector, is particularly vulnerable.

“A.I. will change the labor demand drastically and quickly,” he said. “For many workers, adjusting to the drastic change will be extremely difficult.”

Smart machines will give companies “the opportunity to automate many tasks, redesign jobs, and do things never before possible even with the best human work forces,” according to a report this year by the business consulting firm McKinsey.

Many business leaders dismiss a takeover by machines as “futurist fantasy”.

… Gartner’s 2013 chief executive survey, published in April, found that 60 percent of executives surveyed dismissed as “‘futurist fantasy” the possibility that smart machines could displace many white-collar employees within 15 years.

“Most business and thought leaders underestimate the potential of smart machines to take over millions of middle-class jobs in the coming decades,” Kenneth Brant, research director at Gartner, told a conference in October: “Job destruction will happen at a faster pace, with machine-driven job elimination overwhelming the market’s ability to create valuable new ones.”

Will these changes create a future of leisure and “self-realization”?

Optimists say this could lead to the ultimate elimination of work — an “Athens without the slaves” — and a possible boom for less vocational-style education. Mr. Brant’s hope is that such disruption might lead to a system where individuals are paid a citizen stipend and be free for education and self-realization.

“This optimistic scenario I call Homo Ludens, or ‘Man, the Player,’ because maybe we will not be the smartest thing on the planet after all,” he said. “Maybe our destiny is to create the smartest thing on the planet and use it to follow a course of self-actualization.”

It sounds too good to be true. Although the concept of a future as an “Athens without the slaves” has its appeal, it sounds too fantastic to believe. I wonder what will happen to the segment of the population that lacks the highest level of problem-solving skills.

———

Michael Fitzpatrick, “Computers Jump to the Head of the Class”, New York Times, December 29, 2013.