In contrast to what has occurred during earlier episodes in history, today’s technological advancements are depressing economic growth, according to Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee.

… Brynjolfsson, a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management, and his collaborator and coauthor Andrew McAfee have been arguing for the last year and a half that impressive advances in computer technology—from improved industrial robotics to automated translation services—are largely behind the sluggish employment growth of the last 10 to 15 years. Even more ominous for workers, the MIT academics foresee dismal prospects for many types of jobs as these powerful new technologies are increasingly adopted not only in manufacturing, clerical, and retail work but in professions such as law, financial services, education, and medicine.

There is reason to believe today’s creative destruction differs from historical patterns.

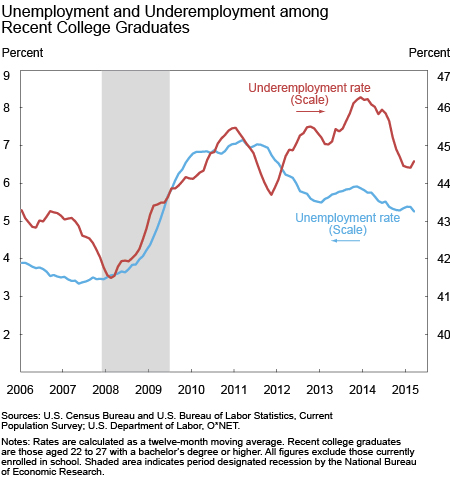

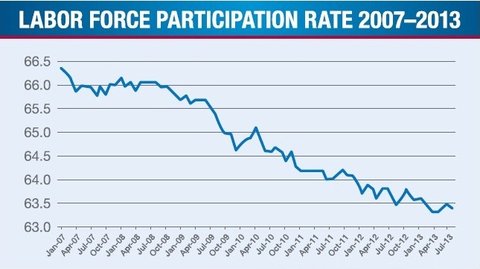

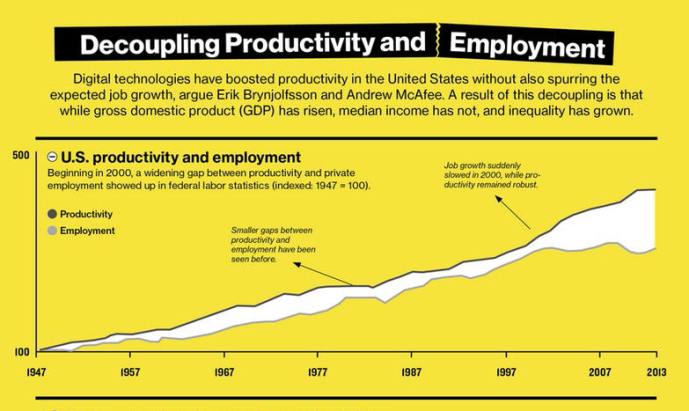

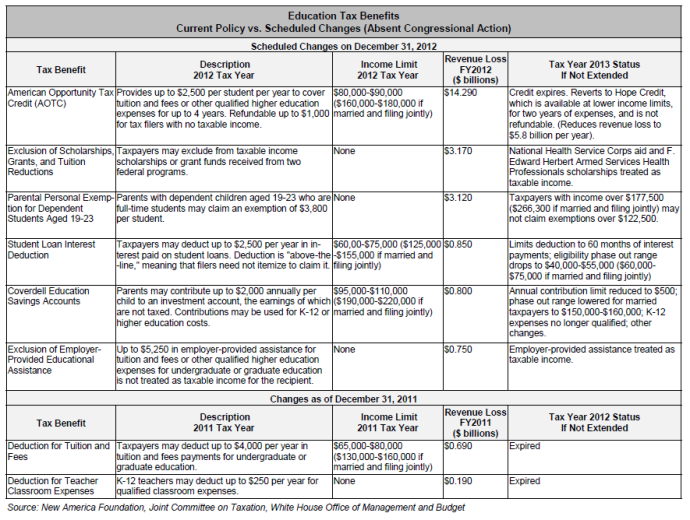

We know that “since the Industrial Revolution began in the 1700s, improvements in technology have changed the nature of work and destroyed some types of jobs in the process”. But this chart showing the “great decoupling” raises questions about the possibility of a new era with long-term periods of involuntary employment for many.

Perhaps the most damning piece of evidence, according to Brynjolfsson, is a chart that only an economist could love. In economics, productivity—the amount of economic value created for a given unit of input, such as an hour of labor—is a crucial indicator of growth and wealth creation. It is a measure of progress. On the chart Brynjolfsson likes to show, separate lines represent productivity and total employment in the United States. For years after World War II, the two lines closely tracked each other, with increases in jobs corresponding to increases in productivity. The pattern is clear: as businesses generated more value from their workers, the country as a whole became richer, which fueled more economic activity and created even more jobs. Then, beginning in 2000, the lines diverge; productivity continues to rise robustly, but employment suddenly wilts. By 2011, a significant gap appears between the two lines, showing economic growth with no parallel increase in job creation. Brynjolfsson and McAfee call it the “great decoupling.” And Brynjolfsson says he is confident that technology is behind both the healthy growth in productivity and the weak growth in jobs.

Many white-collar jobs have been affected, as ‘“digital versions of human intelligence” are increasingly replacing even those jobs once thought to require people’.

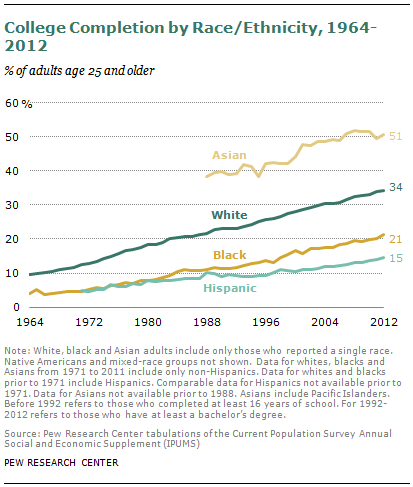

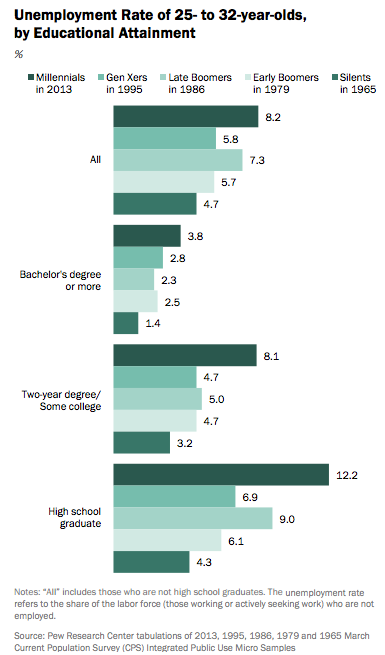

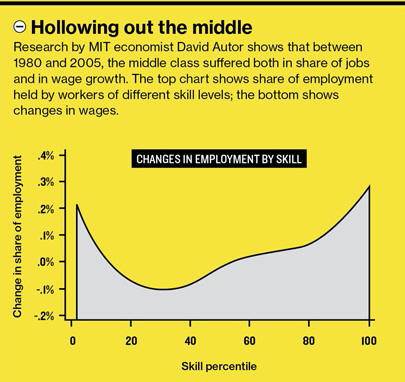

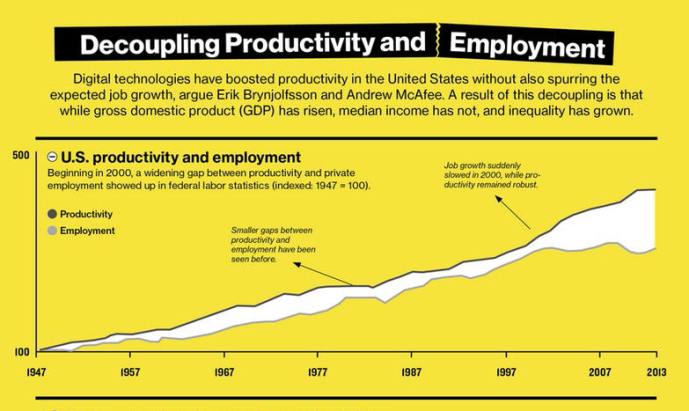

We have seen a “hollowing out” of the middle class.

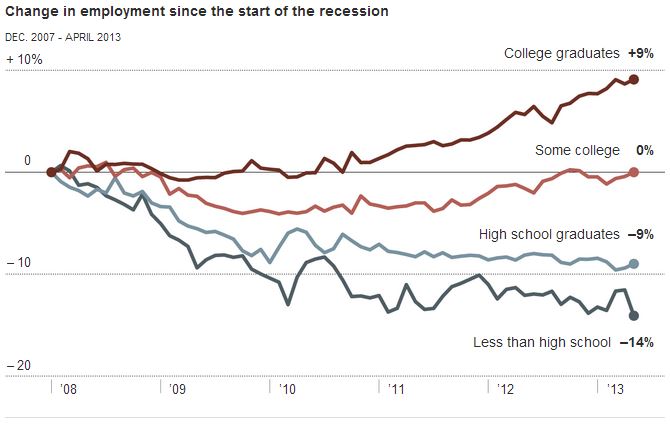

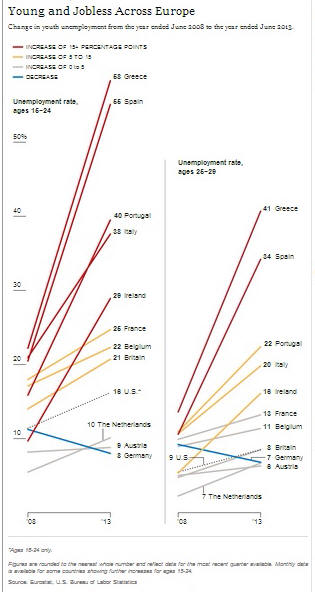

To be sure, Autor says, computer technologies are changing the types of jobs available, and those changes “are not always for the good.” At least since the 1980s, he says, computers have increasingly taken over such tasks as bookkeeping, clerical work, and repetitive production jobs in manufacturing—all of which typically provided middle-class pay. At the same time, higher-paying jobs requiring creativity and problem-solving skills, often aided by computers, have proliferated. So have low-skill jobs: demand has increased for restaurant workers, janitors, home health aides, and others doing service work that is nearly impossible to automate. The result, says Autor, has been a “polarization” of the workforce and a “hollowing out” of the middle class—something that has been happening in numerous industrialized countries for the last several decades. But “that is very different from saying technology is affecting the total number of jobs,” he adds. “Jobs can change a lot without there being huge changes in employment rates.”…

New technologies are “encroaching into human skills in a way that is completely unprecedented,” McAfee says, and many middle-class jobs are right in the bull’s-eye; even relatively high-skill work in education, medicine, and law is affected. “The middle seems to be going away,” he adds. “The top and bottom are clearly getting farther apart.” While technology might be only one factor, says McAfee, it has been an “underappreciated” one, and it is likely to become increasingly significant.

But ‘no one really knows’.

While questions remain on this issue, no one knows for certain if historic patterns of job creation will be repeated. Even Harvard economist Lawrence Katz, whose research has shown how technological advances have consistently led to job creation, tells us that ‘we never have run out of jobs, but it is “genuinely a question”’. Others raise similar doubts.

… “No one really knows,” says Richard Freeman, a labor economist at Harvard University. That’s because it’s very difficult to “extricate” the effects of technology from other macroeconomic effects, he says. But he’s skeptical that technology would change a wide range of business sectors fast enough to explain recent job numbers.

MIT economist David Autor also says “no one knows the cause” for the employment slump.

… The sudden slowdown in job creation “is a big puzzle,” he says, “but there’s not a lot of evidence it’s linked to computers.”

Many of the reasons for sluggish job growth may be rooted in “global trade and the financial crises of the early and late 2000s”. Government policies may play a role. But it is possible that recent technological advances have changed the equation in an unprecedented and permanent manner. Meanwhile, the middle class continues to suffer as politicians, economists, and employers grapple with ‘the great paradox of our era’.

Related: