Are we experiencing an end to the long-term trend of a rising standard of living in our country? Are we due for a “Great Reset” of our economy, one that is inevitable due to the competing interests of workers and consumers?

Tyler Cowen warns “Don’t Be So Sure the Economy Will Return to Normal” and asks “what exactly are we experiencing?”

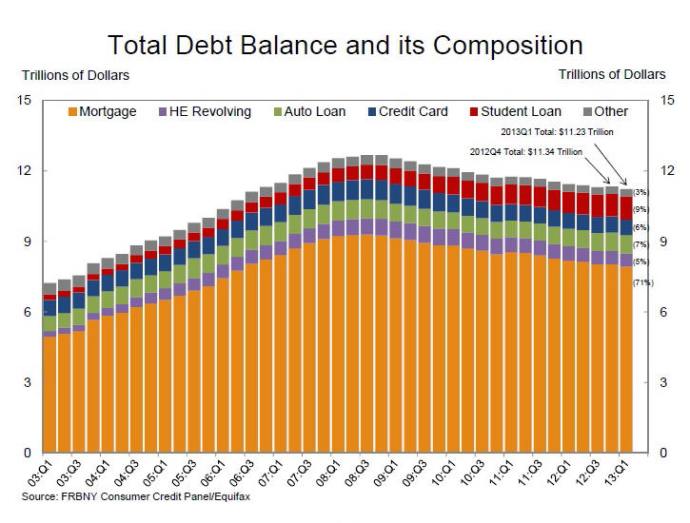

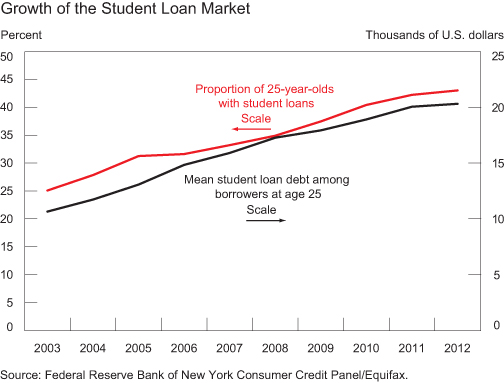

One relatively optimistic view is that observed deficiencies — like slow growth in real wages and the overall economy, persistently low interest rates and low levels of labor participation — are merely temporary. In this view, these problems will dwindle after manageable problems like high levels of public or household debt have been reduced.

Another commonly heard view is that we made the mistake of letting the last recession linger too long, allowing some of its features to became entrenched. That analysis suggests that if we correct past policy errors, whatever they may have been, an underlying normality will re-emerge.

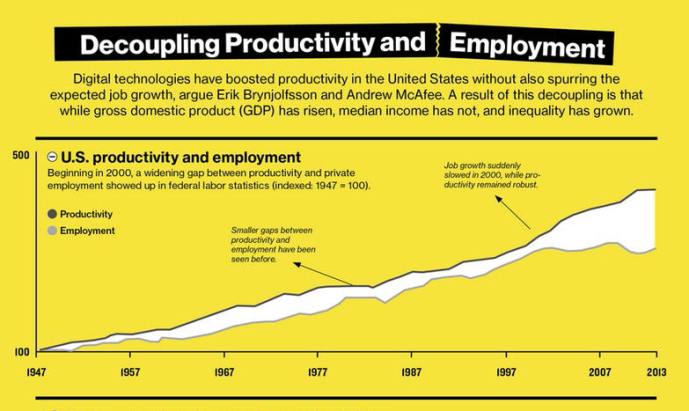

There are some nuggets of truth in both of these arguments, but there is a much more disturbing possibility that could turn out to be more accurate: namely, that the recession was a learning experience that we haven’t fully absorbed. From this perspective, the radical and sudden changes of the financial crisis were early indicators of deep fragility and dysfunctionality.

Slowly but surely, we may be responding to these difficult revelations by scaling back our ambitions for the economy — reinforcing negative trends that were already underway. In this troubling view, we have finally begun to discover some unpleasant truths. Borrowing a phrase from the University of Toronto economist Richard Florida, it’s possible that we are experiencing a “Great Reset.”

A reset is hard for us to see because changes “seem to be gradual and slow”. And new government policies meant to steer the economy “are no more than changes at the margin”.

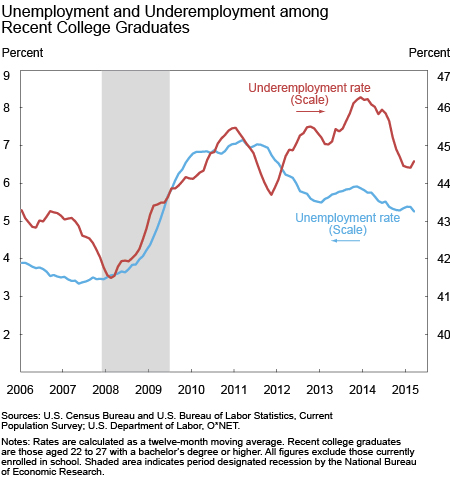

Are millennials bearing the brunt of this reset?

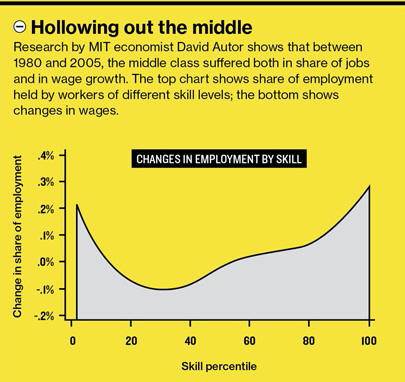

Amid much talk about income inequality and an increasingly two-tier economy, it appears that a “heavy burden of adjustment in the overall labor market is being borne by the young”

… Wages for the typical graduate of a four-year college have dropped more than 7 percent since 2000, and the labor force participation rate of the young has been falling. One consequence is that young people are living at home longer and receiving more aid from their parents. They also seem to be less interested in buying their own homes.

Megan McArdle explains that we brought the “Great Reset” on ourselves, with our desire for rising, stable wages that conflicts with cheap services and goods.

The average American is at the heart of this story — as the victim and as the perpetrator. We suffer as employees because we exert influence as consumers.

Is a reset inevitable?

… The reset may not be fair. It will certainly not be easy. But it may be necessary.

———